Edward Curtis

The Native American in a New Light

Gabriella Rinaldi ’26

Issue: 2

"The Indians of North America are vanishing. There won't be anything left of them and it's a tragedy- a national tragedy," Edward Curtis wrote to George Bird Grinnell, a friend and colleague.1 Curtis was an early twentieth-century Native American photographer, at a time when many Native tribes were experiencing a lot of change, including new white settlers, Indian removal, and the new reservation system. The Cherokees and Creeks were in the process of being forcibly moved away from their home territories, and the Cheyennes, Navajos, Blackfeet, Utes, Crows, and Comaches were only a few of the tribes adjusting to secluded, small reservations or lessened territories set up by the United States government. From 1907 to 1930, Curtis published his collection of photographs in a series called The North American Indian, including over two thousand photographs with captions and additional information that he and his team learned from tribe elders. Curtis's goal was to capture the cultural presence of Native Americans while also displaying how their race was disappearing through his various photographic techniques. “We want the documentary picture of the people and their homeland—a picture that will show the soul of the people,” said Curtis in 1914.2 Although Edward S. Curtis was often criticized for staging his subjects, his photographs and studies in The North American Indian greatly contributed to the archive of Native American culture, which promoted a greater public appreciation for Native American life and history, and counteracted the perception of Native Americans as the inferior race.

Throughout most of his life, Edward Curtis was devoted to Native American photography and documentation. He was born in 1868 near Whitewater, Wisconsin. He began his career at a young age showing interest in photography and even making his own camera. In 1887, he moved to Seattle where he began to photograph Native Americans in the Puget Sound. He began his career as the official photographer for the Edward H. Harriman expedition to Alaska in 1899, where he traveled over 9,000 miles expanding his knowledge of landscape and nature photography. He continued to photograph expeditions into Native American territory, going with George Bird Grinnell on a Montana expedition in 1900, where he documented members of the Blackfeet tribe. Afterward, he spent more time west of the Mississippi, capturing more Native American life. J.P. Morgan, an investment banker, and President Theodore Roosevelt funded Curtis with 75,000 dollars so that he could continue his work. Curtis continued to spend over thirty years traveling across the United States and Mexico with his camera. He captured over 40,000 pictures of Native American people and daily life as well as around 10,000 videos, covering over eighty tribes. In addition to his work, The North American Indian, Curtis filmed a 1914 silent motion picture inspired by Kwakiutl culture, In the Land of the Head Hunters, later known as In The Land of the War Canoes, which now is heavily questioned on its use of staging and over exaggeration. Curtis later died in 1952 in Los Angeles, living to be 84 years old.3

Photographs in The North American Indian brought Native American tribes to a greater audience because of their attractive visuals which alluded to the beautiful and sophisticated nature of Native American life. His knowledgeable execution of artistic photography through his staging and lighting techniques contributed to his images' ability to convey emotion. His skilled use of photographic techniques and placement of subjects further emphasized the complexity of the Native American race. One of these techniques was intentional shadowing, used to deepen the meaning of a picture or to emphasize the contrast between the light and the dark, often on the details in the subject's faces. Another technique he often used was staging his subjects in a pleasing composition, which also helped include several different aspects of Native American culture into one image that was not too overcomplicated. Curtis used staging for artistic appeal, which he received criticism for later on. Despite this, it became a key aspect of his work. Curtis focused on using “Simplicity and Individuality”, as he stated in an article from The Western Trail Illustrated. These core qualities made his images unique to him as well as appealing to a wider audience.4 The photograph “A Chief's Daughter” (Appendix A), which appeared in volume nine of The North American Indian, depicts a charming young Skokomish girl surrounded by neatly woven baskets that contain complex patterning.5 This image was an excellent example of Curtis’ intentional placement of subjects. He positioned the young girl with most of her back facing the camera and her face looking off towards the side to highlight her thoughtfulness and intellect. The woven baskets were purposefully placed around her to show the craftsmanship and complex nature of Skokomish culture. Followers of Curtis’s work during its publishing found appreciation for Native American culture through his skilled display and beautiful visuals. A New York Times article from June 6, 1908, reviewing his collection, reported that “Mr. Curtis has rare qualities as a photographer, alike in his recognition of the groupings, the light, and the shade, the points of view that will make the picture as pleasing as it is truthful, and in his ability to make the picture after he recognizes its value”.6 The article suggested that, through his photographs’ shading and perspective, Curtis was able to reveal the true nature of Native Americans away from stereotypes and create visually appealing images.

Appendix A

“A Chief’s Daughter” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 344

Similarly to “A Chief’s Daughter”, the frontispiece photograph in volume one of The North American Indian, “The Vanishing Race” (Appendix B), Curtis staged in a way that was both alluring and symbolic, leaving the viewer with more questions.7 It depicted several Navajo people riding their horses into a dark and mysterious horizon. The image suggested that the Navajos, along with the Native American race, were beginning to turn away from their culture and tradition, riding, as Curtis stated, “into the darkness of an unknown future.”8 This statement warned viewers of the beauty that would be lost if Native Americans conformed to traditionally white culture, making it a fitting opening picture for Curtis's collection. The image also brought light to the extreme change that Native people experienced during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Most tribes struggled with Indian removal and adjusting to the restrictive reservation system. Many found this transition extremely difficult. “I have listened to many talks from our great father.” said Speckled Snake, leader of the Creek tribe on the topic of white Americans moving into Native territories, “But they always began and ended in this: ‘Get a little further; you are too near me.”9 The unwelcoming nature of white people towards Native American culture was a huge obstacle for Native people as demonstrated through Speckled Snake’s speech. This was one of the main points Curtis tried to show within “The Vanishing Race.” Curtis captured the uncertainty and discrimination that Native people faced through the questions evoked by his stunning and well-thought-out display in “The Vanishing Race”.

Appendix B

“The Vanishing Race” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 36

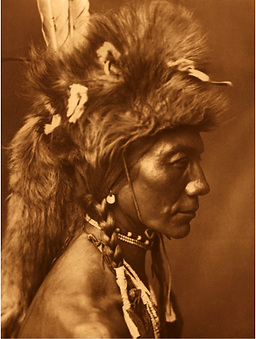

In another example of his detailed imagery and staging, Curtis captured Native American crafts in order to give his audience admiration for the skill of Native artisans. Two particularly prominent groups that Curtis documented the crafts of were the Cowichans and Piegans. The photographs “Masked Dancer” (Appendix C) and “A Cowichan Mask” (Appendix D) from volume nine of The North American Indian, published in 1913, exhibit Cowichan craftsmanship, displaying one of the tribe’s most unique treasures, their masks.10 The images focused on every small detail of the masks: the feathers, the weaving, and the shape. The unique characteristics of the masks, including patterns, carvings, and designs, were eye-catching, and allude to the complexity of Cowichan culture. Also, in many landscape photographs in volume nine of The North American Indian, there were neatly placed canoes, a large part of Cowichan culture and another example of Cowichan craftsmanship. Canoes were one of the most important cultural aspects of the Cowichan people. They were both impressively well-made and a key tool in intertribal warfare, something the Cowichan people were well known for being successful in and proud of.11 Curtis displayed the canoes, which were symbols of the Cowichan people, as almost a part of the environment they sat in. Another example of Curtis showing off the almost regal nature of Native American clothing was in the image, “Tearing Lodge” (Appendix E), which appeared in volume six of The North American Indian, published in 1911.12 It displayed the stunning craftsmanship of Piegan buffalo-skin caps atop the head of Tearing Lodge, Curtis's valued model and informant. Not only did this photograph show the strength of its subject, but the warm texture of the cap’s fur, which caused the viewer to imagine themself feeling or even wearing it. These photographs, and many others throughout Curtis's career, captured the complexity and beauty of the pieces crafted by Native American artisans.

Appendix C

“Masked Dancer- Cowichan” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 341

Appendix D

“A Cowichan Mask” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 340

Appendix E

“Tearing Lodge” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 273

Many followers of Edward Curtis's work noticed and admired how he displayed Native Americans in a way that showed their culture to be just as sophisticated as white culture, making them more relevant to early twentieth-century Americans. “His Indian women are as regal as any New York society matron”, writes Margarett Loke in the January 6, 2002 New York Times. “His men, whether decked out in fancy costumes or wrapped in simple blankets, have the proud bearing and strong gaze of industrialists and bankers. Astride their horses, they look as if they rule the land as far as the eye can see.”13 Curtis's ability to humanize Native Americans in the eyes of a discriminatory America was remarkable. Many strongly supported this cause, including the president himself, Theodore Roosevelt, who was a strong advocate and important funder for The North American Indian. In a 1905 letter to Curtis, Roosevelt wrote:

I regard the work you have done as one of the most valuable works which any American could now do. Your photographs stand by themselves, both in their wonderful artistic merit and in their value as historical documents. I know of no others which begin to approach them in either respect…The publication of the volumes and folios dealing with every phase of Indian life among all tribes yet in a primitive condition, would be a monument to American constructive scholarship of a value quite unparalleled.14

Through his words, Roosevelt demonstrated how important he viewed The North American Indian project, emotionally influenced by the stunning imagery. Roosevelt also noticed how “artistic” and evocative Curtis’s portfolio was. The photographs of Edward Curtis had a serious impact on their viewers, showing who Native Americans were outside of stereotypes and objectification.

Curtis also combatted the idea of an inferior race with his portraits, which captured historical figures important to tribal culture and legends, using Native Americans as icons in order to display their rich history and relate it to the public’s own historical icons. Icons in white culture, like those that we see on American bills and coins, were meant to represent the United States as a whole in a positive and patriotic manner. Curtis attempted to do the same with Native American figures, as a way of advertising them as something America should be prideful of instead of something America should suppress. Curtis used his photographs to capture Cheyenne and Piegan tribal history, which he learned through the stories of elders. Some of his most significant subjects were Little Wolf, a Cheyenne leader who fought against white colonizers for his land, Chief Unistai-poka, also known as White Calf, a legendary warrior and respected Peigan leader, Yellow Kidney, a famous south Peigan warrior, and Princess Angeline, daughter of a respected Duwamish chief and a founding figure of Seattle.15

Little Wolf was one of the strongest Cheyenne leaders and a key figure in Curtis's work, helping the public get a closer understanding of Native American history and struggles. In 1876 the United States Army forced the Northern Cheyenne tribe away from their home to be put into a shared reservation, as a result of them defeating the U.S. Army in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. During the journey to the reservation, many Cheyenne people died because of the extreme traveling conditions, fueling the tribe’s anger even more. In 1878, Little Wolf, combined with the efforts of Dull Knife, led their tribe to escape the reservation. Eventually, U.S. forces tracked them down, but this event led to the Cheyenne people receiving their own reservation later on.16 This story was admirable and heroic. In Curtis's photograph of him (Appendix F), found in volume six, Little Wolf’s face was mostly in shadow, which highlighted his aged face in order to show his wisdom and the struggles he faced in the past, specifically with the reservation system and white settlers.17 Through Little Wolf’s portrait, Curtis showed the power and bravery behind Native American history.

Appendix F

“Little Wolf” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 267

Curtis displayed more Native American warfare history through his documentation of Chief Unistai-poka and Yellow Kidney. Chief Unistai-poka was a successful Piegan chief through the later half of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century. He was well-known amongst Native American tribes for being a fierce warrior.18 Curtis's photograph of him, “White Calf” (Appendix G) displayed him as legendary and stoic. Half of his face was in a shadow, emphasizing the details in his face which alluded to his wisdom. The shadow also made him look mysterious and dangerous, depicting how enemy tribes feared and respected his power. Yellow Kidney was another respected Piegan warrior that Curtis photographed. In his photograph, “Yellow Kidney” (Appendix H), Curtis staged the warrior in a traditional wolf-skin war bonnet, which symbolized Piegan culture's connection to intertribal war, and also displayed impressive craftsmanship. Similarly to the Cowichan tribe, Piegan people were constantly in battle with one another, making war an important aspect of their culture. The lighting of Yellow Kidney’s portrait brings out the muscle definition in both his shoulder and his face, making him look strong and powerful. His head was fully facing towards the right, similar to the positioning of presidents on United States coins.19 Both images show how the two men were worthy of being looked up to and proud of, suggesting that they were no different from white American icons.

Appendix G

“White Calf” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 266

Appendix H

“Yellow Kidney” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 244

Another Native American icon displayed in Curtis's collection was Princess Angeline, also known as Kikisoblu, the daughter of Chief Seattle, a Duwamish leader for whom the city of Seattle, Washington was named . She was born in roughly 1828, making her about 71 years of age when Curtis photographed her in 1899. Throughout her life she was a pioneer in the creation of Seattle, befriending many of its newcomer founding families, as well as a skilled basket weaver.20 Her image (Appendix I) represented the alliance and connection of the Puget Sound Native Americans and the white American settlers. As a personality, Princess Angeline represented the pridefulness and friendliness of Puget Sound Native Americans, something Curtis strived to convey. In her photograph, which was one of the most famous in The North American Indian, Curtis captured her kind gaze and wise eyes. This made her seem more approachable and warm, stating that she, and the Native American race, were positive additions to America as a whole. Through his display, Curtis painted Princess Angeline as yet another Native American icon, specifically for Seattle, where she is still proudly displayed on many postcards. Curtis successfully used her image as a gateway between Native Americans and Seattle, or more broadly, the United States. Through his portraits, he gave Native American culture a chance to be something white America was proud of by turning Native figures into icons.

Appendix I

“Princess Angeline” Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022.

Another way that Curtis brought forth public appreciation for Native American life was by recording information about ceremonies and history from tribe elders and sharing it through articles in Scribner’s Magazine, increasing recognition of the complexity and beauty of Native American culture. Scribner’s Magazine was widely popular in the early twentieth century, with sales ranging between roughly 50,000 to 215,000 during its publishing.21 In the magazine, Curtis eloquently covered a wide range of topics he learned about through his time among different Native American tribes, including burial rituals, daily life, crafted items, language, and historical accounts of traditions and battles. Along with his articles, Curtis included photography to further emphasize the beauty of the culture he discussed. Above the heading of one article, he used the image “Old Crow Man” (Appendix J) displaying long, white feathers atop an old warrior’s war bonnet.22 Curtis used a bright light reflecting off of the feathers as a device to catch the reader’s eye which gave them interest in reading more about the topic. In Curtis's articles, he made sure to paint Native Americans in a positive light that led the audience away from typical stereotypes. For example, in Scribner’s Magazine, 1906, he began his article praising Native people: “The Northwest Plains Indian is, to the average person, the typical American Indian, the Indian of our school-day books- powerful of physique, statuesque, gorgeous in dress, with the bravery of the firm believer in predestination.” His praise was prominent, specifically with the words he used to describe the Native American race, like “statuesque” or “gorgeous”.23 With this approach, he achieved a more positive image of Native people in the heads of the audience as they read more about their day-to-day lives.

Appendix J

“Old Crow Man” Curtis, Edward S. "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Northwest Plains.” Scribner's Magazine, June 1906, 657-71. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/. 659

Throughout his articles, he continued to go into detail about the beauty of Native American life and culture. In a 1906 article, he wrote regarding a ceremonial burial that he witnessed: “In this there was no ‘Boston hat,’ or ‘Boston man's talk,’ but a most beautiful pagan ceremony. The mourners encircled the grave. A high-keyed, falsetto chant by forty voices, rising and falling in absolute unison, sent chills down our spines that hot June day, as did the dismal wail of wintry winds in the pine forests.” His account displayed the sophistication of the ceremony aside from white culture's idea of what sophistication should be, referring to the fact that “In this there was no ‘Boston hat,’ or ‘Boston man's talk,’” but was still beautiful and well thought out.24 His eloquent writing conveyed the beauty of the ceremony that Curtis witnessed, reading almost like a poem because of its many descriptive words and neatly formatted sentences. This approach was useful for showing the reader the true gorgeousness and complexity of the ceremony described.

Curtis again emphasized the sophistication of Native American culture through another 1906 edition of the Scribner’s Magazine, describing the craftsmanship required to create Apache woven baskets. “While decoration, with them is secondary to form and usefulness, every basket is a wonderfully designed piece of handiwork and causes one to wonder how a people apparently so dull to the beautiful can be its creator.” In this statement, Curtis outwardly rejected the idea that Native American people were “dull to the beautiful” or less rich in culture than any white American. He also again brought light to one of the most prominent subjects in his photography, the skillfully woven baskets of Western Native Americans, which he focused on in the photograph “The Chief’s Daughter”.25 In the article Curtis continued to describe the history of the Apache tribe in full depth, information he gathered from tribe elders, which helped to familiarize the readers with tribal culture. The articles Curtis wrote as a whole achieved bringing the many different Native American cultures and traditions into a positive light in the eyes of a more widespread audience.

Edward Curtis's contribution to the documentation of western Native Americans demonstrated that Native American culture was just as important and sophisticated as white American culture. With his expert use of photography techniques and effort put towards the staging in his published photographs, Curtis showed his audience the true complexity and beauty of Native American culture, while raising awareness of the struggles they faced during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He used portraits of important Native American historical figures to show the public their courage as well as their similarity to white American icons. Through his many articles featured in magazines, Curtis continued to put forth a new perspective on Native American people away from stereotypes, reaching thousands of people. Curtis’s work and achievements not only archived the Native American experience and culture of his time, but served as one of the first stepping stones in the journey towards the public acceptance of Native Americans as Americans, and not an alienated race.

Bibliography

"Charles Scribner's Sons: An Illustrated Chronology." Princeton.edu. https://library.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/aids/scribner/index.html#Top.

Curtis, Edward S. "Photography." The Western Trail Illustrated, January 1900. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/_files/ugd/6df1b6_222e829257dd4dac97b14bfa89afca4c.pdf.

Curtis, Edward S. Princess Angeline. Photograph. ARTstor.

Curtis, Edward S. "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Northwest Plains." Scribner's Magazine, June 1906, 657-71. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/.

Curtis, Edward S. "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Southwest." Scribner's Magazine, May 1906, 513-29. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/.

Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022.

Egan, Shannon. "'Yet in a Primitive Condition': Edward S. Curtis's North American Indian." American Art 20, no. 3 (2006): 58-83. JSTOR.

Gidley, M.. "Edward S. Curtis." Encyclopedia Britannica, October 15, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-S-Curtis.

Kikisoblu / Princess Angeline. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.duwamishtribe.org/princess-angeline.

Lagasse, Paul, and Columbia University. "Curtis, Edward Sheriff." In The Columbia Encyclopedia, 8th ed. New York, NY, USA: Columbia University Press, 2018. https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6NjA2NDkx?aid=103994.

Lamar, Howard R. "Curtis, Edward Sheriff." In The New Encyclopedia of the American West. N.p.: Yale University Press, 1998. https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6MjQ5Mjg0OQ==?aid=103994.

Loke, Margarett. "Images That Are Glorious and Gloriously Unreal: An Exhibition of Rare Platinum Prints by Edward S. Curtis Demonstrates His Mythmaking Approach to American Indian Life. Glorious Images, Gloriously Unreal." New York Times (1923-) (New York, N.Y.), 2002, 2-a35. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (92229488).

Mick Gidley. Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian Project in the Field. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=a1588076-75a6-3481-bc6b-c313b9d2995f.

New York Times (1857-1922) (New York, N.Y.). "American Indian in 'Photo History': Mr. Edward Curtis’s $3,000 Work on The Aborigine a Marvel of Pictorial Record." 1908, 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (96848101).

Roosevelt, Theodore. Letter to Edward S. Curtis, 1905. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o193424.

Shamoon Zamir. The Gift of the Face: Portraiture and Time in Edward S. Curtis's the North American Indian. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=b0defa50-9f8d-38a4-b8a7-a2316f297da3.

Touchie, Rodger. Edward S. Curtis above the Medicine Line: Portraits of Aboriginal Life in the Canadian West. Surrey, British Columbia: Heritage House, 2010. PDF.

Waldman, Carl. "Curtis, Edward Sheriff." In Biographical Dictionary of American Indian History to 1900. N.p.: Facts On File, 2000. online.infobase.com/Auth/Index?aid=103994&itemid=WE43&articleId=187842.

The Washington Post (1877-1922) (Washington, D.C.). "Exhibit of Indian Views.: Edward S. Curtis' Pictures to Be Shown in Public." 1909, 14. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Washington Post (144921516).

Footnotes

[1] Touchie, Rodger. Edward S. Curtis above the Medicine Line: Portraits of Aboriginal Life in the Canadian West. Surrey, British Columbia: Heritage House, 2010. PDF. 30

[2] Gidley, M.. "Edward S. Curtis." Encyclopedia Britannica, October 15, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edward-S-Curtis.

[3] Gidley, M.. "Edward S. Curtis."

[4] Curtis, Edward S. "Photography." The Western Trail Illustrated, January 1900. Accessed March 3, 2024. https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/_files/ugd/6df1b6_222e829257dd4dac97b14bfa89afca4c.pdf. 273

[5] Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022.

[6] New York Times (1857-1922) (New York, N.Y.). "American Indian in 'Photo History': Mr. Edward Curtis’s $3,000 Work on The Aborigine a Marvel of Pictorial Record." 1908, 1. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (96848101).

[7] Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios.

[8] Gidley, M.. "Edward S. Curtis."

[9] Mick Gidley. Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian Project in the Field. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=a1588076-75a6-3481-bc6b-c313b9d2995f. 15

[10] Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 338 ; Shamoon Zamir. The Gift of the Face : Portraiture and Time in Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014. 281 ; Touchie, Rodger. Edward S. Curtis above the Medicine Line: Portraits of Aboriginal Life in the Canadian West. Surrey, British Columbia: Heritage House, 2010. PDF. 75-77

[11] Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. ; Touchie, Rodger. Edward S. Curtis above the Medicine Line: Portraits of Aboriginal Life in the Canadian West. 75-77

[12] Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios.; Shamoon Zamir. The Gift of the Face : Portraiture and Time in Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian.

[13] Loke, Margarett. "Images That Are Glorious and Gloriously Unreal: An Exhibition of Rare Platinum Prints by Edward S. Curtis Demonstrates His Mythmaking Approach to American Indian Life. Glorious Images, Gloriously Unreal." New York Times (1923-) (New York, N.Y.), 2002, 2-a35. ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times (92229488).

[14] Roosevelt, Theodore. Letter to Edward S. Curtis, 1905. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.theodorerooseveltcenter.org/Research/Digital-Library/Record?libID=o193424.

[15] Mick Gidley. Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian Project in the Field. 16 ; Touchie, Rodger. Edward S. Curtis above the Medicine Line: Portraits of Aboriginal Life in the Canadian West. 55-56, 46 ; Kikisoblu / Princess Angeline. Accessed February 27, 2024. https://www.duwamishtribe.org/princess-angeline.

[16] Mick Gidley. Edward S. Curtis and the North American Indian Project in the Field. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2003. https://research.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=a1588076-75a6-3481-bc6b-c313b9d2995f. 16

[17] Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. Köln: Taschen, 2022. 266

[18] Touchie, Rodger. Edward S. Curtis above the Medicine Line: Portraits of Aboriginal Life in the Canadian West. Surrey, British Columbia: Heritage House, 2010. PDF. 55-56

[19] Curtis, Edward S., Hans-Christian Adam, and Rolf Fricke. The North American Indian: The Complete Portfolios. 266, 244

[20] Kikisoblu / Princess Angeline. Accessed February 27, 2024.

[21] "Charles Scribner's Sons: An Illustrated Chronology." Princeton.edu. https://library.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/aids/scribner/index.html#Top.

[22] Curtis, Edward S. "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Northwest Plains." Scribner's Magazine, June 1906, 657-71. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/. 659

[23] Curtis, Edward S. "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Northwest Plains." Scribner's Magazine, June 1906, 657-71. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/. 657

[24] Ibid., 660

[25] Curtis, Edward S. "Vanishing Indian Types: The Tribes of the Southwest." Scribner's Magazine, May 1906, 513-29. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.curtislegacyfoundation.org/. 520